Hello and welcome to my first blog post. Thanks for coming to read! With knowledge very much on the educational agenda nowadays, I’m going to throw an idea into the ring about how we might plan in relation to one aspect of historical knowledge: first-order, substantive concepts. In this post, I’m going to suggest an idea for thinking about how planning for progression in first-order conceptual understanding over the course of a curriculum might be framed. I’ll start by jumping straight in with the idea: that we can use the second-order concepts as one framework for planning for progression in first-order conceptual understanding. I will then go into a bit more detail about my rationale, in relation to how progression in historical knowledge has been theorised to date (to the best of my knowledge), and why it makes sense to think about progression in first-order concepts through a framework that explicitly links them to second-order concepts.

A disciplinary framework for progression in pupils’ understanding of first-order concepts

To start with, briefly: what exactly is a first-order concept? First-order concepts can be thought of, perhaps, as the labels we give to the ‘stuff’ of history. Important examples of first-order concepts include: parliament, empire, monarchy or the Church. However, while it may seem like these labels, these first-order concepts, simply and incontestably refer to concrete things that existed in the past, the reality is more unstable. Consider, for example, that the first-order concept of ‘peasant’ is used by historians to refer to groups of people as diverse and distant as those in, for example, Medieval England, nineteenth-century Russia, or twentieth-century Vietnam. Clearly, first-order concepts, like ‘peasant’, are constructs of the historical discipline (or terms borrowed from other disciplines) employed by the historian to impose meaning and structure on the past; they are generalisations that label and encompass an often wide range of manifestations and experiences. Some historians may have decided that these labels, as descriptive generalisations denoting common features or common historical experiences and agencies or institutions with some degree of continuity across time and space, are useful, valid, and acceptable (indeed history would be impossible without generalisations); but interpretative generalisations they are. Indeed, the meaning of many first-order concepts are subject to constant contestation, debate and re-interpretation, such as that of what exactly constitutes an ’empire’. Overall, it is clear that first-order concepts are not unambiguously fixed or ‘given’, and that much historical complexity sits beneath these labels.

Given that first-order concepts are disciplinary constructs, I want to suggest that one way of framing and planning for progression in them could centre on our disciplinary (second-order) concepts. In evaluating whether one’s curriculum builds pupils’ disciplinary understanding of the disciplinary constructs of the first-order concepts, I think that it makes sense to employ our disciplinary (second-order) concepts as a framework. To show what I mean here, I’ll exemplify the process I have in mind in breaking down the first-order concept of ‘the Church’.

Using the second-order concepts as a framework, we could evaluate whether our curriculum, seen as a whole, helps pupils to build a rich historical understanding of the first-order concept of ‘the Church’ by thinking about whether, in what ways, and to what extent it enables pupils (through different contextualised encounters within various historical enquiries) to develop an understanding of:

- How the Church changed over time. (change and continuity)

- How the Church was structured in different societies (and indeed that there were different Churches), and the extent to which it shaped the lives and experiences of different people in similar/different ways. (similarity and difference)

- What the Church meant to particular people and cultures at the time. (historical perspective)

- How the Church was a factor in causing certain events to happen in the way that they did. (causation)

- How the Church was impacted as a consequence of certain events and how changes in the Church impacted societies and people. (consequence)

We can see that through these different second-order concepts, the first-order concept of ‘the Church’ can be analysed and utilised for different historical purposes and to build different kinds of historical understanding: while thinking in terms of similarity and difference seeks to break down the patterns and complexities sitting beneath the label of ‘the Church’, a causal analysis might utilise the generalisation of ‘the Church’ as a unitary institution to assign it causal agency. My guess would be that for the concept of ‘the Church’, many schools’ curricula may be to an extent well-covered on many of these second-order manifestations of this first-order concept, although (from my limited personal experience) pupils might not ‘bump into’ the Church much beyond the seventeenth century nor beyond the English context, and would thus be unable to understand how ‘the Church’ changed over time or how it was structured differently and experienced differently by people beyond these temporal and spatial parameters. I therefore want to emphasise the importance of viewing this second-order framework for progression in first-order concepts with the question of ‘what knowledge?’ always in mind. What second-order understandings of these first-order concepts does your curriculum enable? What understandings does it limit? And, given that curriculum is always limited, are you happy with where these limits currently fall? Meanwhile, again from limited personal experience, my guess would be that there is a lot more work to be done to ensure that crucial first-order concepts such as ‘race’, ‘gender’, and ’empire’ are present within many curricula in ways that enable the broad disciplinary understanding of these first-order concepts encouraged by the framework above.

Rationale

I’ll now explain a bit further my rationale behind the idea of framing progression in first-order conceptual understanding through the second-order concepts, and how this builds upon previous thinking on planning for progression in history through the curriculum. A common way of theorising historical knowledge within history education is through the distinction between first-order and second-order knowledge. First-order knowledge is often called substantive knowledge. This is characterised as the ‘stuff’ of history: names, dates, and concepts (e.g. Church, Parliament, race). Second-order knowledge is often referred to as disciplinary knowledge. This knowledge relates to the kinds of questions historians seek to answer in relation to (and thus giving structure and meaning to) the ‘stuff’ of history and the ways in which historians go about answering them, and is usually framed in terms of second-order or disciplinary concepts. In practice, these two forms of knowledge must come hand-in-hand to be considered meaningful in a disciplinary historical sense. A list of ‘stuff’ (e.g. dates) without any second-order conception of the links between them or the narratives surrounding them is a meaningless list. Knowing a basic definition of the term ’empire’ is historically meaningless unless one can place it within the historical context of second-order narrative or argumentative frameworks (i.e. find ways to relate it in a meaningful and structured sense to other things in history). Similarly, basic knowledge of what second-order concepts are (e.g. abstract knowledge that things change or that events have causes) is not historically meaningful until applied to making sense of actual things from the past (the substantive/first-order).

There is increasingly an effort (given particular impetus, perhaps, by the ‘knowledge-turn’ in education) to theorise what progression in first-order knowledge entails in history. Sometimes this conversation takes place in a way that is divorced from second-order knowledge. At its most basic, this manifests in the idea that first-order progression entails pupils knowing more stuff. Superficially, this makes sense: if substantive knowledge is, in Counsell’s words, ‘fertile, generative and highly transferable’ then knowing more of it is an important part of progressing in historical understanding. However, the reality is more complex.

Issue 1: How to make first-order knowledge historically meaningful

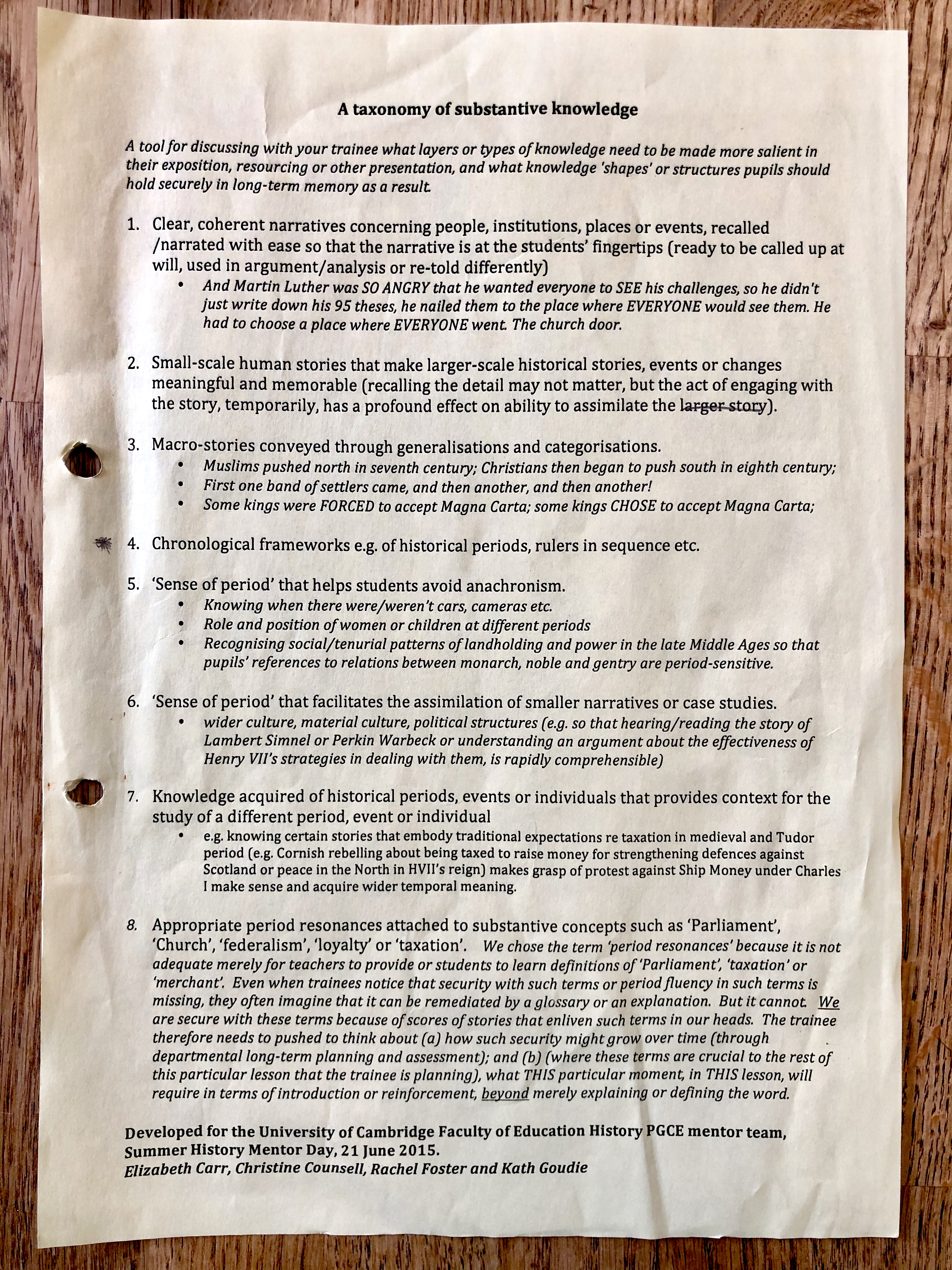

Counsell is clear that progression can only be secured through an interplay between first- and second-order knowledge: yes, more first-order knowledge is an important part of progression, but it cannot be divorced from considerations surrounding the structures through which this knowledge is made meaningful. The taxonomy below can provide a helpful tool for reflecting on whether one’s curriculum builds rich layers of substantive knowledge. In particular, the emphasis on stories and narrative highlights that first-order knowledge can only be made historically meaningful within the context of disciplinary structures (historical narrative/analysis founded on second-order, disciplinary concepts) rather than as lists or definitions. On a curricular scale, it involves thinking about how earlier narratives, and the concepts embedded within them, interlink and enable pupils to make sense of later ones.

This conception of progression can be made to fit well with Fordham and Counsell’s proposition that the curriculum is the progression model. If first-order knowledge is taught within a curriculum that rigorously intertwines first-order and second-order knowledge in meaningful historical enquiries, then it follows that if pupils are learning the curriculum, they are progressing in historical understanding.

Issue 2: What knowledge?

However, even if our curriculum follows the principle that progression through teaching pupils ‘more knowledge’ must involve the intertwining of both first- and second-order knowledge, if not elaborated further the idea that more knowledge means progression still remains a very blunt way of conceptualising progression in historical knowledge. Not least we soon hit the essential question: what knowledge? A number of educators have made strong arguments in relation to this question of ‘what knowledge?’ in Teaching History and elsewhere: Boyd on women’s history; Whitburn and Mohamud on black history; Dennis on the need to avoid tokenism in integrating diverse histories; and a few recent articles on cultural history. Indeed, if pupils are gaining more first-order knowledge, but through a curriculum with an overwhelming political focus on the development of monarchy, taught through the stories of male English monarchs, for example, then pupils’ substantive knowledge is progressing but in a way that is limited to only one narrow area of history. What topics to teach and how to frame the teaching of those topics is clearly a crucial question when thinking about first-order progression.

First-order concepts

The particular issue that I’m focusing on in this blog post is that of how we might think systematically about long-term progression in pupils’ understanding of first-order (substantive) concepts. Within the above taxonomy, this is tackled most explicitly in Point 8.

Point 8 of the ‘taxonomy of substantive knowledge’ states that the curriculum should build ‘period resonances’ for substantive concepts – in other words, it should show pupils what these first-order concepts meant/looked like in particular historical contexts, thus making clear that these meanings and manifestations, to varying extents, differed in different contexts. This theorisation of progression clearly relates to the idea, outlined earlier, that first-order concepts are disciplinary constructs. They are labels that we give to the ‘stuff’ of the past, but crucially labels that do not refer to fixed things. Rather, first-order concepts are labels employed by historians that necessarily impose some kind of coherent meaning to enable historical analysis while sitting atop a large degree of complexity – for example, ‘the Church’ wasn’t exactly the same thing in the 7th century as the 20th century; it isn’t exactly the same in England as in Brazil etc. (The article by Bridges in TH171 is very good at exploring the nature of substantive concepts).

It is the idea of bumping into or encountering important first-order concepts (such as empire, race, Parliament, Church) in different historical contexts, within different rigorous historical enquiries, at different times throughout the curriculum that currently characterises perhaps the best attempts at theorising in a general sense what planning for progression in understanding first-order concepts should entail. I think that this formulation still leaves somewhat open the following question: what kinds of understanding do we want pupils to have built from these varied encounters with particular first-order concepts? Clearly this will vary depending on the particularities of each first-order concept and its place within history – hence the openness of the idea of ‘varied encounter throughout the curriculum’ is to an extent necessary. However, I do think that some generic frameworks can help to structure how we might seek to conceptualise and plan for these particularities. It is here that I think the idea of framing progression in first-order conceptual understanding through the second-order concepts could provide a structured way forward – one that explicitly recognises first- and second-order historical knowledge as inextricably intertwined.

Using the second-order framework to think through Issue 1: How to make first-order knowledge historically meaningful

Do pupils’ multiple and cumulative encounters with particular first-order concepts over the course of the curriculum enable them to understand that those concepts changed over time; applied to varying extents differently in different contexts and in relation to different groups of people (even within the same time period); actually meant something to people at the time, in ways that intertwined with their lives, societies and cultures; and played a role in shaping historical events and their outcomes? Considering pupils’ encounters with first-order concepts with the second-order framework in mind can help us to ensure that our curricula enable pupils over the long term to gain multifaceted historical understandings of first-order concepts and their disciplinary uses and complexities.

Using the second-order framework to think through Issue 2: What knowledge?

The nature and limitations of pupils’ second-order understandings of first-order concepts enabled by the curriculum are inextricably linked to the question of ‘what knowledge?’. Pupils’ understanding of first-order concepts as changeable constructs over time is limited by the time periods in which particular concepts are encountered. Pupils’ understanding that particular first-order concepts can apply both similarly and differently in different societies and to different people is limited by the range of societies and people in relation to which these concepts are encountered. Thus, thinking about the nature and limitations of the second-order understandings of first-order concepts enabled by our curriculum can help us to think through where, and in relation to what knowledge, we want pupils to encounter first-order concepts in our curriculum, if they are to be imbued with broad, diverse and multifaceted historical meanings.

Conclusion

Thinking about first-order progression through the second-order concepts in the way that I have suggested here could be a means for framing thinking around whether one’s curriculum is enabling pupils to progress in their understanding of first-order concepts in various disciplinary ways. Second-order structures give first-order knowledge disciplinary meaning. Does your curriculum as a whole enable pupils to see first-order concepts as disciplinary constructs? In what ways, in relation to what forms of second-order understanding, connected to what knowledge, and with what limitations? Certainly, it would be impossible to make sure – and indeed it is not my intention to suggest – that every single first-order concept is treated in such a way. For certain key concepts, however, I think that this could be just one useful way of framing curriculum conversations around whether the curriculum is enabling pupils to progress in their historical understanding of important first-order concepts.

Bibliography/further reading

Boyd – TH 175 (women’s history)

Bridges – TH171 (substantive concepts)

Chase – https://historyteachermusings.wordpress.com/2020/07/23/assessment-and-progression-in-history/

Counsell – https://thedignityofthethingblog.wordpress.com/

Dennis – TH 165 (diverse history)

Fordham – https://clioetcetera.com/2020/02/08/what-did-i-mean-by-the-curriculum-is-the-progression-model/

Hammond – TH157 (knowledge)

On cultural history – Foster, TH155; Elsdon and Howard, TH176; Olivey, TH176; Benger, TH179

Priggs – TH179 (diverse history)

Whitburn and Mohamud – Doing Justice to History (black history)

An interesting piece, the only thing that jars for me is the terminology: “first-order” and “second-order” seem like poor choices to me, as they imply a hierarchy or ordering, don’t parallel the use of the same terms elsewhere (in say chemistry or logic), and aren’t used in historiographical writing (or at least I’ve never seen them before). I had to keep stopping to remember which was which. Also, Parliament and Church (at least when capitalised) are specific institutions, whereas “empire”, “peasant”, “race” etc. are general categories…

LikeLike

Thanks for reading! The distinction between these two forms of knowledge/the labels applied to them of first/second order and substantive/disciplinary are not my own – they have been developed within the discourse of history education. As to exactly where those labels come from and why they have been chosen (and, more broadly, why historical knowledge has been theorised in this way), I put the question to people far more knowledgeable than me on Twitter and here is the result, if you want to have a look: https://twitter.com/MonsieurBenger/status/1299634589560967169

LikeLike